Quentin Tarantino is a household name at this point. There's no reason to introduce him or to go through his body of work. If you've been alive in the last ten or fifteen years and are interested enough in film to be reading this, I'm going to just make the bet that you know who he is, and are familiar with his work. All that can really be said and all that needs to be said is that many of the movies you see today, much of the writing about movies that you read and everything in ecosystem that can be considered film, has been influenced by Quentin Tarantino. In the last twenty years, no one has put as heavy a foot print on the landscape of cinema. Argue that point as much as you want, but no one with even the slightest amount of objectivity in considering who has and who hasn't influenced film makers, journalism, music in film, marketing, and every aspect of the business and creative side of film culture is going to take it seriously.

Django Unchained is the next step in Tarantino's journey toward taking that legacy in a new direction. That new direction began with Inglorious Basterds, and it's obvious he's pushing forward. He is no longer strictly concerned with telling stories of mythic criminals of some dingy, unseen underground. He's now concerning himself with mythic criminals of dingy, unseen history. It's worth asking whether or not Tarantino felt his rewriting of World War II history didn't cause enough controversy and then decided he'd reach for the most controversial topic in American culture and society. The history of cinema was practically built around WWII stories. In some ways, that makes perfect sense, considering that the medium was coming to prominence as the war was happening. It's also one of the eras in history that's become the most mythologized and in many ways, been the foundation of the American people developing any positive association with their culture and society. It's the war which is undeniably the most just. When the war began, the extent of Nazi horror may not have been known, but it's incredibly hard to make the case that the revelation of Hitlers Final Solution and the extent to which he'd taken his genocidal vision doesn't still make WWII a just war. Whatever else can be said of the various aspects of the war and the way it was handled as a culture and society, the fact that it stopped a genocidal maniac from wiping the Jewish people from the face of the majority of continental Europe is an undeniably good and just thing. Considering how hallowed that history is to American's national conception, the fact Tarantino's rewriting of that history caused only the most minor controversy is a testament to the size of the silhouette he cuts across contemporary culture and cinema.

What could possibly generate more controversy than rewriting the history of World War II? Slavery. Where American culture and society have nearly fetishized WWII, it certainly hasn't attempted very many serious acts of retrospective introspection where slavery is concerned. Culturally, considering the part slavery played in the nations history, it's been essentially overlooked in comparison. Again, the film industry and film as a medium were coming to prominence as the war was actually happening, so in looking at the history of cinema and realizing the gigantic number of films that deal with it isn't really shocking, but to do the same with slavery, look back and count the number of films that deal directly with it as a central part of their narrative, and the degree to which we've been more or less unwilling to consider much of anything about slavery becomes clear. It's not something we like to think or have conversations about on any level.

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Django Unchained (2012, Quentin Tarantino)

Labels:

Christolph Waltz,

controversial,

Django Unchained,

Jamie Foxx,

Leonardo DiCaprio,

Quentin Tarantino,

revenge,

Samuel L. Jackson,

slavery

Tuesday, December 25, 2012

Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976)

|

| Image found at http://rowsdowr.tumblr.com/ |

Labels:

Academy Award winner,

Faye Dunaway,

media,

movie reviews,

Ned Beatty,

Network,

Peter Finch,

Robery Duvall,

Satire,

Sidney Lumet,

television,

William Holden

Monday, November 12, 2012

Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012)

It's an accepted fact at this point that Daniel Craig and Martin Campbell saved the Bond franchise. Casino Royale was enthusiastically received by both critics and audiences that had been wary of a new Bond film when it was announced. The new tone brought Bond into the modern age, and helped to wash the stale taste that had been left in audience's mouths following both Pierce Brosnan and Timothy Dalton's tenures. Even as it left intact many of the things long time fans always look for in a Bond film, Craig and Campbell made the character feel both fresh and familiar at the same time. They focused on the drama of the story and on the characters as much or more than they did giant action set pieces and finding excuses for Bond to use some unbelievable gadget in the middle of the film.

The second film in Craig's term as Bond, Quantum of Solace, Marc Forster took over in the directors seat and proved that following in Martin Campbell's footsteps was no easy task. Quantum wasn't a horrible film, but it was much closer to being both an older variety of Bond film and less interesting. It's definitely not the worst film in the franchise history, but it threatened the good will Casino had built. It shouldn't all be laid at Forster's feet though, as the script written by Paul Haggis, Neal Purvis and Robert Wade was muddled and inconsistent, at best.

With the announcement of Skyfall, there was a sense that if this film didn't deliver the goods, it could actually finally be the end of the Bond franchise. There would always be a hard core fan base, but new fans would be hard to come by and casual movie goers would no longer be interested in the exploits of 007. Skyfall will please the hard core Bond fans as well as casual movie goers looking for some fun at the multiplex.

The second film in Craig's term as Bond, Quantum of Solace, Marc Forster took over in the directors seat and proved that following in Martin Campbell's footsteps was no easy task. Quantum wasn't a horrible film, but it was much closer to being both an older variety of Bond film and less interesting. It's definitely not the worst film in the franchise history, but it threatened the good will Casino had built. It shouldn't all be laid at Forster's feet though, as the script written by Paul Haggis, Neal Purvis and Robert Wade was muddled and inconsistent, at best.

With the announcement of Skyfall, there was a sense that if this film didn't deliver the goods, it could actually finally be the end of the Bond franchise. There would always be a hard core fan base, but new fans would be hard to come by and casual movie goers would no longer be interested in the exploits of 007. Skyfall will please the hard core Bond fans as well as casual movie goers looking for some fun at the multiplex.

Labels:

Ben Whishaw,

daniel craig,

james bond,

Javier Bardem,

Judy Dench,

sam mendes,

Skyfall

Monday, November 05, 2012

Star Bored

George Lucas and the horror that is the second trilogy of Star Wars films did not assuage my love for the original trilogy. Sure, Jedi isn't a great movie by any means, but it still wasnt a horrible film that had some truly great and iconic moments. A New Hope is an amazing piece of popcorn, action/adventure, serial storytelling. The Empire Strikes Back is often cited as the greatest sequel of all time, an argument that can be made quite plausibly and one of the earliest experiences I can remember in a movie theater. I fell in love with this trilogy at an early age, and it is part of what gave me a slavish obsession for cinema, so it takes a whole hell of a lot for me to turn away from it as a fan.

It may have happened though. I may have finally just completely reached the nadir of my ability to handle anything else related to Star Wars. And no, it wasn't that George Lucas sold Lucasfilm to Disney. For about three decades now, the principle difference between Lucasfilm and Disney has been a set of big, round ears and a couple of theme parks. In basically every other way, they've been the same. Consider that Pixar started out under Lucasfilms roof and then made the migration to The Mouse, and that Disney has had a number of Lucasfilm rides in their theme parks. If you're out there getting all pissy over the Disney move now, you're at least twenty years too late. You should have found your scruples earlier.

So, if it wasn't The Mouse becoming Darth Vader's new master and it wasn't that abomination that was the second trilogy, what could possibly have made me decide that just maybe it's time to let it go and just cut the cord with all things Star Wars? It's the absolutely insane reaction from the nerdhood in the film press. As someone who has spent many years now, pouring over the details of upcoming projects, tidbits from behind the scenes, stories of studio strife and the general commentary of the internet film press, I can say that of all the insanity I've seen, and that hasn't been an inconsequential amount, I've never seen anything as ridiculous as this.

It may have happened though. I may have finally just completely reached the nadir of my ability to handle anything else related to Star Wars. And no, it wasn't that George Lucas sold Lucasfilm to Disney. For about three decades now, the principle difference between Lucasfilm and Disney has been a set of big, round ears and a couple of theme parks. In basically every other way, they've been the same. Consider that Pixar started out under Lucasfilms roof and then made the migration to The Mouse, and that Disney has had a number of Lucasfilm rides in their theme parks. If you're out there getting all pissy over the Disney move now, you're at least twenty years too late. You should have found your scruples earlier.

So, if it wasn't The Mouse becoming Darth Vader's new master and it wasn't that abomination that was the second trilogy, what could possibly have made me decide that just maybe it's time to let it go and just cut the cord with all things Star Wars? It's the absolutely insane reaction from the nerdhood in the film press. As someone who has spent many years now, pouring over the details of upcoming projects, tidbits from behind the scenes, stories of studio strife and the general commentary of the internet film press, I can say that of all the insanity I've seen, and that hasn't been an inconsequential amount, I've never seen anything as ridiculous as this.

Labels:

actors,

directors,

editors,

film news,

film sites,

internet film community,

movie news,

movie reviews,

writers

Thursday, October 25, 2012

The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2012)

Joaquin Phoenix spent two full years essentially trolling the living hell out of the press with I'm Still Here. He spent two years, in character, every single time he appeared outside of his home. It was all a stunt, but it demonstrates a level of dedication that is either deeply troubling or worthy of substantial admiration.

That level of dedication is clear in The Master, in a way that is profoundly effective. Phoenix has been the subject of critical praise throughout his career, but absolutely nothing he's done compares to the level of performance he is able to achieve here. It's flat out amazing. Nothing else can express it.

If that weren't a good enough reason to see The Master, there's Philip Seymour Hoffman. Another of this generations most respected actors, who has managed to find his way into a roles that have demonstrated he's a gifted actor with the ability to make characters feel real and grounded on a range that is impressive because of how rare it is. This is the best work he's ever done.

The two men spend eighty-five to ninety percent of the films running time on screen together. doing this strangely dysfunctional dance in the creation of a relationship that is at times deeply troubling, but only in just how well it portrays the reality of this kind of interaction. There's a level of emotional honesty in the script that gives Hoffman room to display all of his range, and more. It also gives Phoenix the chance to so fully embody a character that it crawls right up to the line of being unsettling to consider that he is acting, and not actually the person he's portraying on screen.

That level of dedication is clear in The Master, in a way that is profoundly effective. Phoenix has been the subject of critical praise throughout his career, but absolutely nothing he's done compares to the level of performance he is able to achieve here. It's flat out amazing. Nothing else can express it.

If that weren't a good enough reason to see The Master, there's Philip Seymour Hoffman. Another of this generations most respected actors, who has managed to find his way into a roles that have demonstrated he's a gifted actor with the ability to make characters feel real and grounded on a range that is impressive because of how rare it is. This is the best work he's ever done.

The two men spend eighty-five to ninety percent of the films running time on screen together. doing this strangely dysfunctional dance in the creation of a relationship that is at times deeply troubling, but only in just how well it portrays the reality of this kind of interaction. There's a level of emotional honesty in the script that gives Hoffman room to display all of his range, and more. It also gives Phoenix the chance to so fully embody a character that it crawls right up to the line of being unsettling to consider that he is acting, and not actually the person he's portraying on screen.

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Paranormal Activity 4 (Henry Joost, Ariel Shulman, 2012)

If there's one thing you need to know about Paranormal Activity 4, it's that there's nothing new in front of the lens, under the moon or anywhere else for that matter. There isn't anything in the latest installment of the Halloween season behemoth franchise that you haven't seen in the previous installments. The question is, did you like what you saw in the first three movies? If you did, the chances are pretty good that you're going to enjoy this as well.

It doesn't succeed in carrying the series mythology forward in a substantial way like the third film, and most of the scares are variations on things the first three films have already succeeded in using to cause a theater full of people to jump, yelp and sometimes scream in fright. At the same time, if you're looking for a fun time in a theater full of people who are anticipating having the crap scared out of them, and they enjoy that idea, you're in luck.

Let's face it, the Paranormal Activity series hasn't reinvented the horror genre with any of it's installments. It has succeeded because it's been like an amusement park ride. A large group of people get together, and agree it's perfectly acceptable to act in a way they would not find it acceptable to be seen acting under any other circumstances, like frightened children. Henry Joost and Ariel Shulman have succeeded in delivering that experience again. There are some seriously great scares peppered throughout the film.

It doesn't succeed in carrying the series mythology forward in a substantial way like the third film, and most of the scares are variations on things the first three films have already succeeded in using to cause a theater full of people to jump, yelp and sometimes scream in fright. At the same time, if you're looking for a fun time in a theater full of people who are anticipating having the crap scared out of them, and they enjoy that idea, you're in luck.

Let's face it, the Paranormal Activity series hasn't reinvented the horror genre with any of it's installments. It has succeeded because it's been like an amusement park ride. A large group of people get together, and agree it's perfectly acceptable to act in a way they would not find it acceptable to be seen acting under any other circumstances, like frightened children. Henry Joost and Ariel Shulman have succeeded in delivering that experience again. There are some seriously great scares peppered throughout the film.

Labels:

Ariel Shulman,

demons,

ghosts,

halloween favorites,

haunted house,

Henry Joost,

horror,

Paranormal Activity 4,

possession

Saturday, October 20, 2012

Sinister (Scott Derrickson, 2012)

It's that time of year. The Halloween season is upon us. The horror industry is kicking things into high gear as everyone is a little more willing to venture out and attempt to find a film that's going to scare them out of their wits.

One of the many offerings this Halloween season is Sinister, directed by Scott Derrickson, who is also credited as having written the screenplay, with C. Robert Cargill (Massawyrm to readers of Ain't It Cool News, who's gone on to write for his own site, Hit Fix). The trailer and marketing material suggest a film about haunted home movies, starring Ethan Hawke.

Derrickson's most well known film to date is The Exorcism of Emily Rose, which drew it's strength from taking a different perspective on the possession genre and a particularly strong performance from Jennifer Carpenter. Given that and the fact that Cargill is an enthusiastic and unabashed cinema devotee whose work I've been reading for years, I thought it worth giving Sinister a chance. If nothing else, I'd be using my dollar to cast a vote for movies made by people who love them instead of being made by people who only see them as vehicles used to extract dollars from the pockets of unsuspecting consumer audiences.

One of the many offerings this Halloween season is Sinister, directed by Scott Derrickson, who is also credited as having written the screenplay, with C. Robert Cargill (Massawyrm to readers of Ain't It Cool News, who's gone on to write for his own site, Hit Fix). The trailer and marketing material suggest a film about haunted home movies, starring Ethan Hawke.

Derrickson's most well known film to date is The Exorcism of Emily Rose, which drew it's strength from taking a different perspective on the possession genre and a particularly strong performance from Jennifer Carpenter. Given that and the fact that Cargill is an enthusiastic and unabashed cinema devotee whose work I've been reading for years, I thought it worth giving Sinister a chance. If nothing else, I'd be using my dollar to cast a vote for movies made by people who love them instead of being made by people who only see them as vehicles used to extract dollars from the pockets of unsuspecting consumer audiences.

Labels:

C. Robert Cargill,

home movies,

horror,

Scott Derrickson,

Sinister

Monday, September 03, 2012

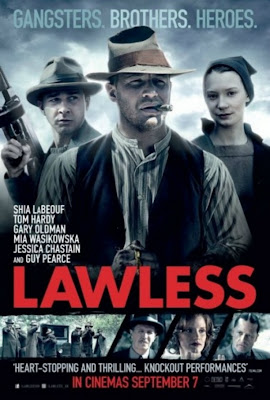

Lawless (John Hillcoat, 2012)

Lawless is saved from being a boring, lifeless gangster movie by it's performances. Tom Hardy, Guy Pearce, Jessica Chastain, and yes, even Shia Lebouf succeed in creating a fun, entertaining, not very substantial entry into American film industries favorite genres, gangster/outlaw cinema.

Tom Hardy is quickly headed toward being regarded as one of the best actors of his generation. He's taken on a number of roles that differ in significant ways and succeeded in making them all memorable, genuine and unpredictable. He does it again playing Forrest Bondurant, the leader of the bootlegging Bondurant clan during Prohibition. Based on a true story, chronicled in Matt Bondurant's novel "The Wettest County in the World", Hardy manages to create an enigmatic, charismatic stillness as the center of the films events. Shia Lebouf is definitely the films lead, but Hardy's character is really the heart of the story.

Tom Hardy is quickly headed toward being regarded as one of the best actors of his generation. He's taken on a number of roles that differ in significant ways and succeeded in making them all memorable, genuine and unpredictable. He does it again playing Forrest Bondurant, the leader of the bootlegging Bondurant clan during Prohibition. Based on a true story, chronicled in Matt Bondurant's novel "The Wettest County in the World", Hardy manages to create an enigmatic, charismatic stillness as the center of the films events. Shia Lebouf is definitely the films lead, but Hardy's character is really the heart of the story.

Labels:

action,

Bootlegging,

drama,

Franklin County Virginia,

gangster movies,

Gary Oldman,

Guy Pearce,

Lawless,

Nick Cave,

outlaw movies,

Shia Lebouf,

Tom Hardy,

Tom Hillcoat

Sunday, August 05, 2012

The Tall Man (Pascual Laugier, 2012)

Pascual Laugier made a splash on the international film scene in 2008 with his rapaciously brutal horror epic Martyrs. It was one of the most controversial films of the year. It was also a film attempting to reach for something much more than the average gore soaked fare it was lumped in with by many critics. Whether or not it managed to grasp what it was reaching for is largely subjective, based on what exactly the viewer was bringing into the film. (Note: In the interest of both transparency and to let readers know what I thought of the film, my review for Martyrs can be found here, and I can also tell you it made my list of the fifty best horror films of the decade and the list of the seventy-five best films of the decade. I'm an enthusiastic fan.) Laugier was lauded and lambasted, in classic faux-outrage fashion, for the films gore, it's graphic depiction of violence and it's general idea. He did not develop an immediately warm and cozy relationship with either the film press or the critical community.

With his English language debut The Tall Man (originally and more aptly titled The Secret), Laugier makes one thing very clear. He's not interested in making standard horror films. In what might be a feat of imagination in today's film and general media environment, he may have also developed a new storytelling structure or a new formula. Martyrs and The Tall Man, have their basic structure in common, but the films are extremely different in every other way.

With his English language debut The Tall Man (originally and more aptly titled The Secret), Laugier makes one thing very clear. He's not interested in making standard horror films. In what might be a feat of imagination in today's film and general media environment, he may have also developed a new storytelling structure or a new formula. Martyrs and The Tall Man, have their basic structure in common, but the films are extremely different in every other way.

Labels:

horror,

jessica biel,

pascual laugier,

suspense,

the tall man

Saturday, July 07, 2012

Thunder Soul (Mark Landsman, 2010)

Let's get one thing out of the way. If you have ever remotely enjoyed documentaries, you should see Thunder Soul immediately. There are only a handful of reasons that a person shouldn't see this film, and all of them have more to do with self righteous than they actually do with the quality of this film or the story it has to tell.

With that out of the way, let's move on. Thunder Soul is the story the Kashmere High School Band, and the reunion that would become Kashmere High School Alumni Band, and their band leader, Conrad "Prof" Johnson. They became the best high school band in the country, and one of the best funk bands in the country, high school, amateur, professional or otherwise.

The great thing about Thunder Soul is that it isn't the kind of cloyingly sweet feel good tripe that so many documentaries of it's ilk become. Is it "feel good"? Absolutely. Does it have something positive to say about it's subjects and their experience? Yes. What it doesn't do is reach for some kind of overarching metaphor about the human condition and beat the audience with some kind of positivist message. It tells the story of these people, the context in which the events it portrays take place and it always lets them speak for themselves. In that way, it becomes something the viewer can digest in their own time, and in many ways, find their own meaning in. There's a whole lot that can be culled from the experience and actions of the Kashmere High School Alumni Band, but it's up to the audience to decide what exactly about those things are most worthy of being given that time and thought. Mark Landsman has enough respect for both his subjects and his audience to leave all of that up to them.

Without doubt, this is one of the most vibrant and human music documentaries I've ever seen. Because it's not weighed down with trying to debunk or uphold a band or scene that is already enshrined in the popular imagination, it has no need to deal with the kind of sensationalism that is unfortunately is a part of the music industry to such a degree that very few music documentaries are able to tell a complete story about their subjects without contending with it. It's a warm film, without shearing off the warts of the subjects in order to present some fantasized ideal that could never exist.

This is going to be one of the shortest reviews I've ever posted. The reason for that being, that so long as you don't find good funk music offensive somehow (and I'm hoping that the number of people who still fall in that category is infinitesimal at this point), there's absolutely nothing about this doc to dislike. It's a vibrant film, celebrating the art of musicianship, community, education, and the kind of disciplined hard work that comes with doing anything as well as this band played funk music. More than being worth the time it took to watch it, I felt I didn't want it to end, which is an extremely rare quality for a documentary. If you have any taste for documentary film, see this one A.S.A.P.

With that out of the way, let's move on. Thunder Soul is the story the Kashmere High School Band, and the reunion that would become Kashmere High School Alumni Band, and their band leader, Conrad "Prof" Johnson. They became the best high school band in the country, and one of the best funk bands in the country, high school, amateur, professional or otherwise.

The great thing about Thunder Soul is that it isn't the kind of cloyingly sweet feel good tripe that so many documentaries of it's ilk become. Is it "feel good"? Absolutely. Does it have something positive to say about it's subjects and their experience? Yes. What it doesn't do is reach for some kind of overarching metaphor about the human condition and beat the audience with some kind of positivist message. It tells the story of these people, the context in which the events it portrays take place and it always lets them speak for themselves. In that way, it becomes something the viewer can digest in their own time, and in many ways, find their own meaning in. There's a whole lot that can be culled from the experience and actions of the Kashmere High School Alumni Band, but it's up to the audience to decide what exactly about those things are most worthy of being given that time and thought. Mark Landsman has enough respect for both his subjects and his audience to leave all of that up to them.

Without doubt, this is one of the most vibrant and human music documentaries I've ever seen. Because it's not weighed down with trying to debunk or uphold a band or scene that is already enshrined in the popular imagination, it has no need to deal with the kind of sensationalism that is unfortunately is a part of the music industry to such a degree that very few music documentaries are able to tell a complete story about their subjects without contending with it. It's a warm film, without shearing off the warts of the subjects in order to present some fantasized ideal that could never exist.

This is going to be one of the shortest reviews I've ever posted. The reason for that being, that so long as you don't find good funk music offensive somehow (and I'm hoping that the number of people who still fall in that category is infinitesimal at this point), there's absolutely nothing about this doc to dislike. It's a vibrant film, celebrating the art of musicianship, community, education, and the kind of disciplined hard work that comes with doing anything as well as this band played funk music. More than being worth the time it took to watch it, I felt I didn't want it to end, which is an extremely rare quality for a documentary. If you have any taste for documentary film, see this one A.S.A.P.

Labels:

documentary,

education,

funk,

music,

Thunder Soul

Monday, July 02, 2012

Red, White and Blue (Simon Rumley, 2010)

Let's get something straight from the very beginning. Red, White and Blue is not, at all, what it's synopsis might lead you to believe it is. It's not that the synopsis is in any way wrong or misleading, but more that writer director Simon Rumley has found a way to take that basic story and turn it upside down, inside out, then stuff the viewer inside of it and shake it all up with unremitting fury.

In mainstream studio cinema, there are certain tropes everyone recognizes and understands. Good guys make sarcastic remarks, things blow up, the bad guys get their due. It is what it is, we all know this.

Independent cinema has it's own tropes, but since most of us have spent the majority of our lives becoming intimately familiar with them, we don't always recognize them as readily. The idea of a story being built around a coincidental "intersection of lives" is indeed one of the independent film communities favorite tropes. The lives intersecting here are the "Red", "White" and "Blue"on the poster image. The result of that intersection is what the movie is about, and it goes through a few phases before it reaches it's climax, a third act that was distressing and engrossing.

This had to be an independent film. I rarely say that, but in all honestly, I can't see this film ever being made by a major studio and actually succeeding in finding it's way to release. For any audience which is easily offended or is sensitive to many of the cultural taboos that studio films purposely avoid, they wouldn't make it through the first third of this film, much less to the point where that degree of "indecency" in the films first act begins to make any real sense. The first act contains a few scenes of relatively graphic sex. It's hard to say much about it without giving too much away, but it's definitely meant to provoke a response from the viewer. It's not graphic in the violent sense, but it does present sex in a non-traditional way and it's really frank about the degree to which sex is kind of awkward and visceral, and not at all the glamorous act so often portrayed on screen. There are three different sex scenes in the first fifteen minutes of the movie, and that number of them, combined with their overall tone and atmosphere make them extremely discomfiting to watch.

Credit should be given to Rumley on this though, it's a bold decision. The majority of films (and basically any class or text about writing fiction will tell writers to do this) begins in a way that is designed to make the central character(s) sympathetic. It's supposed to get the audience to root for the protagonist or at least to see them in some light that will make it possible for the audience to root for them, to like them and sympathize with them as the film or story progresses. Rumley more or less ditches that whole idea immediately. Amanda Fuller's Erica (the red in the poster) is not an immediately likable character, to put it mildly. Fuller succeeds in making her character completely believable, and ultimately understandable by the end of the film. It's a role that definitely took some courage for any young actor to tackle, and she pulls it off extremely well. In those first few minutes there is the threat of Rumley being a condescending jack-ass who hates his characters and has constructed an obvious, hammer the audience in the head with the message movie. I was getting close to bailing out and turning it off. There isn't a variety of film I dislike more than that one, whether I agree with the general idea or message being put across or not.

Thankfully, Red, White and Blue changes tracks when the second central character is introduced, and those first few minutes of the film begin to fall into what appears to be another context. It's a genuine evolution of the relationship between these characters that begins to show Amanda Fuller's character, Eric in a new light, but also succeeds in presenting Noah Taylor's Nate (the blue in the poster) from a few different perspectives as well. What's clear as that relationship begins to emerge is that these are two extremely, tragically damaged people. Having succeeded in creating those first fifteen minutes of uncomfortable viewing, Rumley takes the discomfort in a different direction completely here. It begins to touch on and realistically portray the kind of interpersonal dynamics that these two characters would necessarily have in the evolution of that relationship, and it's hard to watch because of just how badly they navigate it. Noah Taylor is an actor many people would recognize, having had smaller parts in a number of well known films, but he's unrecognizable here. On top of that, he's fantastic. I didn't connect him with his other roles until I sat down to write this review, and when I did, I was honestly blown away. It's probably good that he isn't recognizable, because few people would probably guess the actor in those parts in those other movies was capable of what he pulls off here. The depth of intensity he portrays here is a thing of beauty. Like John Hawkes in Winter's Bone, this could be a real emergence for an actor that has been criminally overlooked. As the relationship between Nate and Erica progresses, it began to look as if the film was going to start relying on the well worn cliché of damaged people wandering an ugly, unsafe world and finding safety, comfort and love in each other. It doesn't. This isn't that movie either.

Just when it seems the film has settled into becoming the kind of recognizable story most audiences seeing it are going to expect, it changes track again. This time, it changes it's focus almost entirely, and begins to follow our third character, Marc Senter's Franki (the white in the poster). It's questionable as to whether or not Franki is quite as damaged as Nate and Erica certainly seem to be, but at best, he's a bit of a slacker and kind of lost. As his story progresses though, we're seeing him become the kind of damaged person that Nate and Erica are, and probably even more so. Senter does a good job with Franki's journey, and he conveys a combination of both vulnerability and a vague aire of being just about to reach the edge of complete desperation.

Fifteen minutes into the movie, I had no idea where it was going. Forty-five minutes in, I still could not have predicted it was going to come to the climax that it does. The thing worth respecting about all of that though, is that by the time the film does actually end, it doesn't seem false. It's not a "trick" or "gimmick" ending. By the time the film ends and the credits start to roll, it makes perfect sense. It's also not the kind of "perfect sense" in which it all just seems too neat and simple either. There were a number of different places where this story could have gone in a completely different direction.

Probably the most interesting thing about the film though, is that it ends up where it does, and all of that makes as much sense as it does because this isn't a film about people who are achieving some kind of victory at it's climax. It's a film about the mistakes very broken people make, and how those mistakes play out in their own lives and the lives of others. There is no hero here. There are three protagonists, and all three of those characters are also the antagonists. All of it makes logical sense in the context of who the characters are, and with the narrative this film is telling, that's quite a feat.

In a strange way, even as the last twenty minutes of the film are the only depictions of violence (some of which takes place off screen, and that which takes place on screen is actually both a part of the characters and integral to the overall success of the story), it's a film that really is about the question of how exactly we decide what we call violence. Why do we refer to one thing as violence, and a different act that is as damaging to a human being (in a way that is physical, but not in the conventional understanding of how we discuss physical violence) isn't called violence? All three of these characters do things that are beyond the pale of what is considered acceptable human behavior, and those acts all have serious consequences for other people. While definitely not being the kind of behavior the audience is going to condone, in the context it's presented, all of their actions make sense given what we know about the characters as well. The beauty of it being that because they are three dimensional characters, not just one dimensional caricatures, it never comes across as an empty attempt at shock or a necessary plot point to drive the story forward. It makes sense because of who they are, and from that perspective it makes it harder to judge them quite as harshly.

Red, White and Blue isn't a film for everyone. It's bleak, uncomfortable journey into the unfortunate circumstances surrounding the very understandable mistakes of three people who are damaged in tragic, heart breaking ways. What it is not is predictable tripe that any well tread movie goer is going to have a solid handle on in the first twenty minutes. It's both an extremely unconventional horror film and a deeply unsettling drama, without the normal melodrama so often found in films that try to achieve that synthesis. It's an unexpected little gem that manages to subvert expectations in ways that are completely organic and true, and to also be a deeply human story that succeeds in asking intelligent questions without being paternalistic, preachy or patronizing. Simon Rumley has succeeded in creating a very strong film with a subtle hand at storytelling and sure hand at the technical aspects as well. He'll be someone to watch in the future. You can catch this one on Netflix "Watch Instantly", but if you decide you want to own it (as I think I have), come on back and use the link. It's deeply appreciated.

In mainstream studio cinema, there are certain tropes everyone recognizes and understands. Good guys make sarcastic remarks, things blow up, the bad guys get their due. It is what it is, we all know this.

Independent cinema has it's own tropes, but since most of us have spent the majority of our lives becoming intimately familiar with them, we don't always recognize them as readily. The idea of a story being built around a coincidental "intersection of lives" is indeed one of the independent film communities favorite tropes. The lives intersecting here are the "Red", "White" and "Blue"on the poster image. The result of that intersection is what the movie is about, and it goes through a few phases before it reaches it's climax, a third act that was distressing and engrossing.

This had to be an independent film. I rarely say that, but in all honestly, I can't see this film ever being made by a major studio and actually succeeding in finding it's way to release. For any audience which is easily offended or is sensitive to many of the cultural taboos that studio films purposely avoid, they wouldn't make it through the first third of this film, much less to the point where that degree of "indecency" in the films first act begins to make any real sense. The first act contains a few scenes of relatively graphic sex. It's hard to say much about it without giving too much away, but it's definitely meant to provoke a response from the viewer. It's not graphic in the violent sense, but it does present sex in a non-traditional way and it's really frank about the degree to which sex is kind of awkward and visceral, and not at all the glamorous act so often portrayed on screen. There are three different sex scenes in the first fifteen minutes of the movie, and that number of them, combined with their overall tone and atmosphere make them extremely discomfiting to watch.

Credit should be given to Rumley on this though, it's a bold decision. The majority of films (and basically any class or text about writing fiction will tell writers to do this) begins in a way that is designed to make the central character(s) sympathetic. It's supposed to get the audience to root for the protagonist or at least to see them in some light that will make it possible for the audience to root for them, to like them and sympathize with them as the film or story progresses. Rumley more or less ditches that whole idea immediately. Amanda Fuller's Erica (the red in the poster) is not an immediately likable character, to put it mildly. Fuller succeeds in making her character completely believable, and ultimately understandable by the end of the film. It's a role that definitely took some courage for any young actor to tackle, and she pulls it off extremely well. In those first few minutes there is the threat of Rumley being a condescending jack-ass who hates his characters and has constructed an obvious, hammer the audience in the head with the message movie. I was getting close to bailing out and turning it off. There isn't a variety of film I dislike more than that one, whether I agree with the general idea or message being put across or not.

Thankfully, Red, White and Blue changes tracks when the second central character is introduced, and those first few minutes of the film begin to fall into what appears to be another context. It's a genuine evolution of the relationship between these characters that begins to show Amanda Fuller's character, Eric in a new light, but also succeeds in presenting Noah Taylor's Nate (the blue in the poster) from a few different perspectives as well. What's clear as that relationship begins to emerge is that these are two extremely, tragically damaged people. Having succeeded in creating those first fifteen minutes of uncomfortable viewing, Rumley takes the discomfort in a different direction completely here. It begins to touch on and realistically portray the kind of interpersonal dynamics that these two characters would necessarily have in the evolution of that relationship, and it's hard to watch because of just how badly they navigate it. Noah Taylor is an actor many people would recognize, having had smaller parts in a number of well known films, but he's unrecognizable here. On top of that, he's fantastic. I didn't connect him with his other roles until I sat down to write this review, and when I did, I was honestly blown away. It's probably good that he isn't recognizable, because few people would probably guess the actor in those parts in those other movies was capable of what he pulls off here. The depth of intensity he portrays here is a thing of beauty. Like John Hawkes in Winter's Bone, this could be a real emergence for an actor that has been criminally overlooked. As the relationship between Nate and Erica progresses, it began to look as if the film was going to start relying on the well worn cliché of damaged people wandering an ugly, unsafe world and finding safety, comfort and love in each other. It doesn't. This isn't that movie either.

Just when it seems the film has settled into becoming the kind of recognizable story most audiences seeing it are going to expect, it changes track again. This time, it changes it's focus almost entirely, and begins to follow our third character, Marc Senter's Franki (the white in the poster). It's questionable as to whether or not Franki is quite as damaged as Nate and Erica certainly seem to be, but at best, he's a bit of a slacker and kind of lost. As his story progresses though, we're seeing him become the kind of damaged person that Nate and Erica are, and probably even more so. Senter does a good job with Franki's journey, and he conveys a combination of both vulnerability and a vague aire of being just about to reach the edge of complete desperation.

Fifteen minutes into the movie, I had no idea where it was going. Forty-five minutes in, I still could not have predicted it was going to come to the climax that it does. The thing worth respecting about all of that though, is that by the time the film does actually end, it doesn't seem false. It's not a "trick" or "gimmick" ending. By the time the film ends and the credits start to roll, it makes perfect sense. It's also not the kind of "perfect sense" in which it all just seems too neat and simple either. There were a number of different places where this story could have gone in a completely different direction.

Probably the most interesting thing about the film though, is that it ends up where it does, and all of that makes as much sense as it does because this isn't a film about people who are achieving some kind of victory at it's climax. It's a film about the mistakes very broken people make, and how those mistakes play out in their own lives and the lives of others. There is no hero here. There are three protagonists, and all three of those characters are also the antagonists. All of it makes logical sense in the context of who the characters are, and with the narrative this film is telling, that's quite a feat.

In a strange way, even as the last twenty minutes of the film are the only depictions of violence (some of which takes place off screen, and that which takes place on screen is actually both a part of the characters and integral to the overall success of the story), it's a film that really is about the question of how exactly we decide what we call violence. Why do we refer to one thing as violence, and a different act that is as damaging to a human being (in a way that is physical, but not in the conventional understanding of how we discuss physical violence) isn't called violence? All three of these characters do things that are beyond the pale of what is considered acceptable human behavior, and those acts all have serious consequences for other people. While definitely not being the kind of behavior the audience is going to condone, in the context it's presented, all of their actions make sense given what we know about the characters as well. The beauty of it being that because they are three dimensional characters, not just one dimensional caricatures, it never comes across as an empty attempt at shock or a necessary plot point to drive the story forward. It makes sense because of who they are, and from that perspective it makes it harder to judge them quite as harshly.

Red, White and Blue isn't a film for everyone. It's bleak, uncomfortable journey into the unfortunate circumstances surrounding the very understandable mistakes of three people who are damaged in tragic, heart breaking ways. What it is not is predictable tripe that any well tread movie goer is going to have a solid handle on in the first twenty minutes. It's both an extremely unconventional horror film and a deeply unsettling drama, without the normal melodrama so often found in films that try to achieve that synthesis. It's an unexpected little gem that manages to subvert expectations in ways that are completely organic and true, and to also be a deeply human story that succeeds in asking intelligent questions without being paternalistic, preachy or patronizing. Simon Rumley has succeeded in creating a very strong film with a subtle hand at storytelling and sure hand at the technical aspects as well. He'll be someone to watch in the future. You can catch this one on Netflix "Watch Instantly", but if you decide you want to own it (as I think I have), come on back and use the link. It's deeply appreciated.

Labels:

Amanda Fuller,

drama,

horror,

Marc Senter,

Noah Taylor,

Red White and Blue,

Simon Rumley

Friday, June 29, 2012

Cropsey (Barbara Brancaccio, Joshua Zeman; 2009)

The most famous documentary relating to a wrongful prosecution is The Thin Blue Line. Errol Morris' 1988 documentary was responsible for a man being released from death row for a crime that he had been convicted of through a combination of overzealous prosecution and poor police work. It's not only a masterpiece of the documentary film genre, but a strong example of the degree to which the combination of film and journalism can actually do something important. Wrongful convictions, especially those which involve a sentence of either life in prison or death, can force a society to question even it's most basic assumptions of justice.

Cropsey, is a film that journeys into similar territory. It begins with what was a local legend for Staten Island, New York. The legend gives the film it's name. It begins with Willowbrook State School. Willowbrook has a storied history, beyond Staten Island that reaches into the history of the treatment of mental illness and the treatment of the disabled. Beginning in 1965, outcry over the treatment of patients in Willowbrook became a centerpiece of a movement to change the way that people with disabilities and mental illness were treated. Willowbrook State School was held up as the example of what shouldn't have ever been done, and what should never be done again. Footage from inside Willowbrook, even for someone who has spent a lifetime delving into every nook and cranny of the strange world of horror fiction in all of it's incarnations, is among the most disturbing things I've ever seen. It's terrifying, heartbreaking, and really lives up to the fullness of the word nightmarish.

In Staten Island, an urban legend had grown, and children were told to stay away from the old ground of Willowbrook, and the park that surrounded it, especially at night. They'd be told that Cropsey would come to get them. Cropsey was supposed to be either a former patient or orderly of Willowbrook that had returned there and would be waiting for unsuspecting children.

The film makers Barbara Brancaccio and Joshua Zeman both grew up in Staten Island, and even as they'd grown up in different parts of the borough, and hadn't known each other as children, they'd both been told the story repeatedly. They'd both made the obligatory pilgrimages to Willowbrook, searching for whatever it is children search for in the dark places whose storied histories frighten them. The film begins with that urban legend and then it takes on the real life events that were the basis of that legend.

As the story unfolds, a story of missing children and a community near crazed with grief and fear, it doesn't becomes more and more convoluted and confusing, instead of becoming clearer. Most of it deals with the question of guilt as it relates to the man who was arrested for the kidnapping and murder of many of the children who'd gone missing, and the story veers back and forth from seeming to point to the man as guilty at some points, and at others to suggest he might be innocent and that the actual killer may still be free. The film makers have done exhaustive work finding as many of the witnesses and participants in the searches and the investigation and covering every aspect of the case as possible. A few different theories end up coming to the surface, and being that the case took place during the Eighties, the obligatory Satanic cult theory show is suggested and was apparently even believed to be the main motive by a number of police, despite the fact that it began with a local preacher who claimed to have visions of children being sacrificed on altars. To their credit, the film makers present this as just as much a part of the original case as any other part, because at the time, it would have been, and even in the present day, there are still a number of people who seem to believe it's the real explanation and motive for the kidnappings and murders.

Cropsey really touches on that childhood fear of the stories we're told about monsters hiding in closets or under the bed. It also does a great job of making it perfectly clear just how the disappearances and the murders effected the community. Beyond all of that though, it touches on something incredibly interesting and that is important in a larger context. It touches on the way that facts and legends can start to become intermixed. It also touches on the lengths people will go to in order to create some sense of understanding the truly horrible and tragic aspects of life. The way the stories began to intertwine as facts and suspicions became almost interchangeable presents a picture almost as frightening as the disappearances and murders themselves, given the possibilities inherent in a community turning it's focus away from what it can prove to what it believes.

This is an extremely well made and deeply compassionate documentary that deals with some of the more horrifying aspects of humanity in an empathetic way that isn't demanding judgment, but is just trying as hard as it can to understand as well as it can. The result, really, becomes a film that pulls in many different topics and ideas and through that empathy never seems as if it's sloppy, reaching or ill advised or stepping over the line into sensationalism. It's a great example of how approaching a documentary with the right prospective is more important than the budget it has or just how slickly produced it is. I'd stack this up against any of the documentaries by the industries most recognizable names any day.

Cropsey, is a film that journeys into similar territory. It begins with what was a local legend for Staten Island, New York. The legend gives the film it's name. It begins with Willowbrook State School. Willowbrook has a storied history, beyond Staten Island that reaches into the history of the treatment of mental illness and the treatment of the disabled. Beginning in 1965, outcry over the treatment of patients in Willowbrook became a centerpiece of a movement to change the way that people with disabilities and mental illness were treated. Willowbrook State School was held up as the example of what shouldn't have ever been done, and what should never be done again. Footage from inside Willowbrook, even for someone who has spent a lifetime delving into every nook and cranny of the strange world of horror fiction in all of it's incarnations, is among the most disturbing things I've ever seen. It's terrifying, heartbreaking, and really lives up to the fullness of the word nightmarish.

In Staten Island, an urban legend had grown, and children were told to stay away from the old ground of Willowbrook, and the park that surrounded it, especially at night. They'd be told that Cropsey would come to get them. Cropsey was supposed to be either a former patient or orderly of Willowbrook that had returned there and would be waiting for unsuspecting children.

The film makers Barbara Brancaccio and Joshua Zeman both grew up in Staten Island, and even as they'd grown up in different parts of the borough, and hadn't known each other as children, they'd both been told the story repeatedly. They'd both made the obligatory pilgrimages to Willowbrook, searching for whatever it is children search for in the dark places whose storied histories frighten them. The film begins with that urban legend and then it takes on the real life events that were the basis of that legend.

As the story unfolds, a story of missing children and a community near crazed with grief and fear, it doesn't becomes more and more convoluted and confusing, instead of becoming clearer. Most of it deals with the question of guilt as it relates to the man who was arrested for the kidnapping and murder of many of the children who'd gone missing, and the story veers back and forth from seeming to point to the man as guilty at some points, and at others to suggest he might be innocent and that the actual killer may still be free. The film makers have done exhaustive work finding as many of the witnesses and participants in the searches and the investigation and covering every aspect of the case as possible. A few different theories end up coming to the surface, and being that the case took place during the Eighties, the obligatory Satanic cult theory show is suggested and was apparently even believed to be the main motive by a number of police, despite the fact that it began with a local preacher who claimed to have visions of children being sacrificed on altars. To their credit, the film makers present this as just as much a part of the original case as any other part, because at the time, it would have been, and even in the present day, there are still a number of people who seem to believe it's the real explanation and motive for the kidnappings and murders.

Cropsey really touches on that childhood fear of the stories we're told about monsters hiding in closets or under the bed. It also does a great job of making it perfectly clear just how the disappearances and the murders effected the community. Beyond all of that though, it touches on something incredibly interesting and that is important in a larger context. It touches on the way that facts and legends can start to become intermixed. It also touches on the lengths people will go to in order to create some sense of understanding the truly horrible and tragic aspects of life. The way the stories began to intertwine as facts and suspicions became almost interchangeable presents a picture almost as frightening as the disappearances and murders themselves, given the possibilities inherent in a community turning it's focus away from what it can prove to what it believes.

This is an extremely well made and deeply compassionate documentary that deals with some of the more horrifying aspects of humanity in an empathetic way that isn't demanding judgment, but is just trying as hard as it can to understand as well as it can. The result, really, becomes a film that pulls in many different topics and ideas and through that empathy never seems as if it's sloppy, reaching or ill advised or stepping over the line into sensationalism. It's a great example of how approaching a documentary with the right prospective is more important than the budget it has or just how slickly produced it is. I'd stack this up against any of the documentaries by the industries most recognizable names any day.

Labels:

Cropsey,

documentary,

Staten Island,

Willowbrook

Sunday, June 10, 2012

Prometheus (Ridley Scott, 2012)

Prometheus is not Alien. If that fact is something you can understand and embrace, walking into the theater, the chances are you're going to enjoy the two hour running time.

If this isn't a fact you can both understand and embrace, the odds are in favor of disappointment.

It's a good film. It is a very different film than the film that is responsible for the franchise. It is, in more ways than not, a much bigger, much more ambitious film than Alien. Ridley Scott is a different man now than he was when he made Alien, and there's obviously a lot on his mind. Prometheus is, in another way, classic Ridley Scott as well. Some of Scott's better films have managed to tackle Big Ideas and present them in interesting ways while also being entertaining pieces of popular art. Blade Runner and Black Hawk Down being two of the better examples of Scott's ability to tame his narrative ambitions enough to produce films that have some depth and weight, yet find their way into the hearts of people who aren't looking for little more than entertainment in a movie theater. There's a lot of venom out there for Black Hawk Down, because it gets lumped in with other action-ish films dealing with the military as a simplistic piece of nationalist propaganda, but in reality, there's a good deal more to that film than the kind of empty headed, uncritical flag waving of the films it so often gets categorized with. What it isn't, is a preaching, preening work of anti-war, anti-military or anti-government propaganda, which is often what it's detractors seem most upset with it for. Personally, I don't like to be preached at via celluloid, whether or not I find some sympathy with the sentiments being expressed. If I want preaching, I'll go to a rally or go to a church. Decent narrative art, much less good or great narrative art, doesn't need to resort to communicating to the least common denominator in order to say something worth while. Even as Ridley Scott has directed a few films that seem to have been driven by little more than bloated arrogance (I'm looking at you Robin Hood), he has proved he can direct films with Big Ideas in a subtle and deft way.

I have a feeling Prometheus is going to suffer a similar fate in many ways, separate and apart from the fact that there's going to be a large contingent of people who are going to be disappointed that Ridley Scott didn't deliver Alien wrapped in a new package and tied in a sparkling bow made of the latest special effects. As absurd as science fiction often is when looked at from the perspective of literalism, if Scott had attempted to make Prometheus in the vein of being nothing more than a spectacle of summer movie going, it would have been laughably absurd. Big Idea science fiction can slip into being deeply, unattractively, unknowingly campy very easily, and Prometheus avoids any of that, even as there are a few moments of definite gallows humor.

If this isn't a fact you can both understand and embrace, the odds are in favor of disappointment.

It's a good film. It is a very different film than the film that is responsible for the franchise. It is, in more ways than not, a much bigger, much more ambitious film than Alien. Ridley Scott is a different man now than he was when he made Alien, and there's obviously a lot on his mind. Prometheus is, in another way, classic Ridley Scott as well. Some of Scott's better films have managed to tackle Big Ideas and present them in interesting ways while also being entertaining pieces of popular art. Blade Runner and Black Hawk Down being two of the better examples of Scott's ability to tame his narrative ambitions enough to produce films that have some depth and weight, yet find their way into the hearts of people who aren't looking for little more than entertainment in a movie theater. There's a lot of venom out there for Black Hawk Down, because it gets lumped in with other action-ish films dealing with the military as a simplistic piece of nationalist propaganda, but in reality, there's a good deal more to that film than the kind of empty headed, uncritical flag waving of the films it so often gets categorized with. What it isn't, is a preaching, preening work of anti-war, anti-military or anti-government propaganda, which is often what it's detractors seem most upset with it for. Personally, I don't like to be preached at via celluloid, whether or not I find some sympathy with the sentiments being expressed. If I want preaching, I'll go to a rally or go to a church. Decent narrative art, much less good or great narrative art, doesn't need to resort to communicating to the least common denominator in order to say something worth while. Even as Ridley Scott has directed a few films that seem to have been driven by little more than bloated arrogance (I'm looking at you Robin Hood), he has proved he can direct films with Big Ideas in a subtle and deft way.

I have a feeling Prometheus is going to suffer a similar fate in many ways, separate and apart from the fact that there's going to be a large contingent of people who are going to be disappointed that Ridley Scott didn't deliver Alien wrapped in a new package and tied in a sparkling bow made of the latest special effects. As absurd as science fiction often is when looked at from the perspective of literalism, if Scott had attempted to make Prometheus in the vein of being nothing more than a spectacle of summer movie going, it would have been laughably absurd. Big Idea science fiction can slip into being deeply, unattractively, unknowingly campy very easily, and Prometheus avoids any of that, even as there are a few moments of definite gallows humor.

Labels:

Alien,

Charlize Theron,

dystopian fiction,

evolutionary fiction,

Guy Pearce,

Idris Elba,

Michael Fassbender,

Noomi Rapace,

Prometheus,

Ridley Scott,

science fiction

Sunday, April 15, 2012

Cabin In The Woods (Drew Goddard, 2012)

My first reaction to Cabin In The Woods is that I now completely understand why it sat on a shelf for three years. It's going to inspire a rabid following. The throngs of movie goers who go to see something like Transformers: Dark Of The Moon and think it's a really great movie, are not going to like this film... at all. I wouldn't be shocked if it inspires a visceral hatred in that audience. It has no interest in being that kind of movie, though I could be also be wrong about that, because on a purely visceral level, it delivers an out of control freight train of imagery and sound. Unlike a Transformers film though, it does so completely coherently. The real problem for that audience is going to be that it's going to make them uncomfortable in certain ways the majority of the casual movie going public is not interested in being subjected to, whether they're completely conscious of the reason they feel uncomfortable or not. It's all there, and even as the subtext of the film is never, for one second, ham handed and patronizing, it's there. On top of that, the unconventional nature of the narrative is going to throw them for a loop, which means the subconscious picking up on that subtext isn't going to be lulled into a quiet coma or easily ignored. The chances are pretty good that this is going to be a film with a life like that of Fight Club. It will inspire a rabid fan base among some of those who have seen it in theaters and who will evangelize for it enough that it will be a much more successful film once it's release to Video On Demand, Blu-Ray and DVD. At the same time I do think a lot of people are probably going to have a vicious hatred for this movie.

This film does succeed in doing something incredibly rare though. It succeeds in it's narrative and pure presentation, while also being a kind of weird experiment at exactly the same time. Most films that make the attempt to do both, end up being successful with one aspect, and missing aspects of the other part in a way that is noticeable during the film's viewing. Much of what works in this film is due to the fact that it has a manically paced forward motion that does not slow down for a second. There is so much packed into this film that it's kind of astounding that writers Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard were able to pull all of it off as well as they have. More often than not, when a film is paced this quickly, and bubbles with this much energy, it's a method used to cover up the things in the film that don't work. If the film makers don't give the audience enough time to digest what they've just seen and throw some entirely new scenario, dilemma or set piece at the audience before they have time to really think about it, the audience doesn't think about it until after the film is over. If they enjoyed the experience of seeing the film, and realize later that things don't quite work or really fit together when they think about it, they're still much more likely to be charitable toward the film because the initial experience was satisfying. That's not what's happening with Cabin In The Woods. This is the kind of film that will hold treasures on repeated viewings, little things the interested viewer didn't pick up initially. The real beauty of that pace is that in this instance, there is no realization that there is this kind of grand experiment playing out (in the narrative, and also between the film and the audience) until the film is already over. If anything is going to save this film with the kind of mass audience film studios generally love to court, it's going to be the fact that the pacing and the writing make it an extremely entertaining experience. The tension and the laughs, combined with the Mach 4 speed of the film translate into something that feels at first like the most fun forms of pure cinema entertainment. Considering it later is going to reveal just how much is going on in this film, and just how well all of that works within the narrative and in the films structure.

That's just the entertainment value of the film, of which there is more than enough to go around. The real feat is that there's a smartly written comment on film making, horror films, and audience expectations deeply woven into the texture of the film and the surface narrative. That narrative subtext works just as well or better than the narrative on the surface, and for the audience that's been following the film since production was announced five years ago, it adds yet another layer by being a reflexive comment on the fact that it sat on a shelf for three years because no distributor was willing to take a gamble on it until Joss Whedon was attached to The Avengers (and having now finally gotten the opportunity to see Cabin In The Woods, I'm even more excited about The Avengers). This isn't to say Cabin In The Woods has any pretensions about being either an art film or some kind of masterwork of socially conscious film making, but that it's creative team aren't bound to the idea that film has to necessarily be either entertaining or have something else to say. It's a pretty perfect example of the idea that both can be achieved in the same film with some deft writing and direction.

Cabin In The Woods isn't a horror film, even though that's more or less how it's being marketed. It's part horror film, part science fiction, part adventure movie and part meta commentary, jam packed into 95 minutes. Lionsgate's marketing department deserves a pass on this one though, because they're not necessarily misleading the audience with the trailers and commercials they've put out. Giving away any more than they do would be a detriment to the audience experience of seeing the film for the first time. That said, in some aspects, the marketing campaign is going to work in their favor, and in some aspects, it's not. For the kind of horror audience that has a dedicated love of the genre as a whole (including literature) it's going to be one of the more exciting and thoughtful films they've seen in a really, really long time. There's been a lot of comparison to Scream in the reviews and press about the film, but ultimately, that's both a lazy and unfair comparison. Cabin In The Woods is taking a perspective on horror films closer to that which Network took toward television news. It's satire and it's commentary aren't as omnipresent, but it is very much the same kind of laughing at, making fun of and being somewhat disgusted and horrified by. Some people will probably also connect the film with some degree of commentary about reality television, and though I can see how one might find that in the film to a certain degree, it's a tenuous connection, and I think it's pretty obvious that's not exactly what the film makers intended. Like a number of the films which have attempted to make some commentary about reality television, Cabin In The Woods definitely has a few questions for it's audience, but that's a larger cultural connection not specific to either this film or reality television more generally. Tonally, and as far as the goal the film is attempting to achieve by it's conclusion, it probably most resembles Fight Club. There's some really dark humor, some shockingly graphic content, some hard questions asked of the audience that will be uncomfortable for the casual film goer, but will present some really interesting discussions and ideas for the kind of movie goer who appreciates it when a film does attempt to engage them this way and still sees film as a viable medium for asking these kinds of questions.

The performances in the film are all at least effective. There's no one in this film that sucks, and that may not sound very complimentary, but there's so much going on and the film is moving at such a rapid pace, there isn't a whole lot of time for any single performance to really shine. None of the performances feels false or out of place, none of them rip the audience out of the experience of the films narrative. Richard Jenkins and Bradley Whitford are given the best lines and the meatiest parts in the film when the narrative is taken as a whole, but even they don't have the kind of premium screen time that's going to highlight exactly how good they are in the roles they're given. They've been given the best comedic moments in the film and they're also central to both the surface narrative and the meta narrative under the surface. There's a lot of potential in a feature length comedy pairing the two actors, because they compliment each other really well, are recognizable enough to most audiences that their familiarity will convey the kind of trust an audience puts in it's lead actors, but not so recognizable they come with the kind of associations that are attached to more recognizable leading men.

IMDB has the estimated budget for the film at thirty million dollars, and every cent of it is on the screen. For your average American film in the multiplex, thirty million isn't really all that high of a budget, but Goddard makes great use of it. Considering the production values that so many celluloid crap fests churn out with a considerably larger budget, Cabin In The Woods looks and feels like much more expensive film than it ultimately was. It's packed with effects of the digital and practical variety. There are some pretty gory moments, and the third act of the film is a wonderland for horror fans, in every conceivable way. The effects are all effective and like the performances aren't necessarily meant to be eye popping or revelations of any kind on their own, but serve the story exactly the way they're meant to. There were no moments of really bad effects eliciting the kind of grown I'm prone to in a film with a budget of this size. Again, there are films with budgets twice and three times Cabin In The Woods that have much, much worse effects, both digitally and practically.

For those who might be interested in the meta narrative aspects of the film, but might also shy away from the horror aspects, don't be too worried. There are a few really bloody sequences in the film, but they Goddard doesn't linger on the gore in the way many horror films do. They have a purpose, they convey that purpose and then he's done with them. As a whole, the film skirts the line between the expectations of gore hounds and a more general audience admirably. If there's any place it might disappoint two prospective audiences simultaneously, it's in the gore aspect. General audiences will probably find it slightly gorier than is to their liking, and the gore hounds of the horror set will probably walk away having hoped for slightly more blood and bodily dismemberment. There are very few instances of violence occurring in the actual frame, so the opportunities to present gore fans with the kinds of effects they thrill and wonder at are minimum.

So who should really go to see Cabin In The Woods, and what audiences are actually most likely to really enjoy it? It's a tough question to answer. There's a whole lot to enjoy about the film. It's definitely entertaining, and isn't self indulgent enough for the meta narrative to get in the way of general audience appreciation for it. At the same time, it flouts the conventions of the horror genre (and the film many people are going to be expecting to see as a result of the marketing) in a way that's going to seriously piss some of them off or leave them feeling unsatisfied with the theater experience of the film. Others are going to find fault with the lack of exposition it dedicates to one of the larger aspects of the story. It's all there, definitely, but there's a good deal of information that's either inferred through dialog and isn't directly explained or is portrayed visually. The kind of audience that likes it's story spoon fed to it is going to be alienated by the degree to which it treats them like they should be able to keep up without all that exposition. Anyone who finds the concept of meta narratives deeply annoying, is going to dislike it.

Anyone whose taste in movies fits those descriptions shouldn't go see it. It's definitely worth seeing, and worth the price of admission, but for those audiences, it's probably best to catch it on VOD, Netflix or what ever other form they choose. It's the kind of film that's worth seeing for what you don't like about as much as for what you do.

The audience most likely to get enjoyment out of this film is the one that is least cynical about film in general. The casual theater goer who walks into any theater, hoping they're going to get ninety minutes or two hours worth of entertainment and expects nothing more, is going to enjoy it. There's no shortage of entertainment value. There are aspects of this film that are going to blow those people away, and they're going walk away saying, "Holy shit. I didn't think you could do that." The third act is going to give them something they never knew they wanted.

In a similar vein, those of us with a more dedicated love of film as something more than just idle entertainment (and that's not meant as a slight to those who do see it that way), and are able to go into a theater and hope that a film succeeds at what it sets out to do (and see anything beyond pure entertainment as an added bonus) are going to find this a really satisfying experience. There's enough going on in the meta aspect to be worth the time of unpacking it and considering it. It's well crafted and obviously a labor of love by two quixotic film makers. This audience will appreciate it for at least what it tries to do, even if they find it a little light on the more satirical commentary aspects.