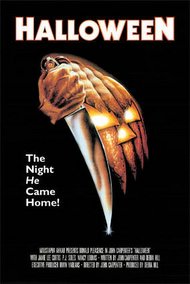

It's the grand daddy of the slasher genre of horror film. It's the one which has spawned a thousand imitators, some of which were good (most of which were horrible), but none of which come close to the class or style of the original. Like "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre," "Halloween" has long been beaten on by critics for violent content and bloody imagery. My first thought about this is to question whether or not these guys are even watching the movies they are speaking or writing about. The two films are nearly bloodless, and have less violence than your average night of prime time television.

It's the grand daddy of the slasher genre of horror film. It's the one which has spawned a thousand imitators, some of which were good (most of which were horrible), but none of which come close to the class or style of the original. Like "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre," "Halloween" has long been beaten on by critics for violent content and bloody imagery. My first thought about this is to question whether or not these guys are even watching the movies they are speaking or writing about. The two films are nearly bloodless, and have less violence than your average night of prime time television.The genesis of Halloween began when producer Irwin Yablans decided he wanted to make a horror film. He came up with an idea taking place in one night, about someone stalking babysitters because he felt it would be easy to identify with, "Everyone has been a baby sitter or been baby sat." Once he'd settled on that, he thought it might be even more interesting to set the film on Halloween. His first thought being someone would already have used the name, he went to researching, and found to his amazement that no one had used the name. Not only that, but the word Halloween had never been used in a title before, so he set about finding someone to write the film.

Yablans had done a small action/drama called "Assault on Precinct 13" with a young screenwriter/director named John Carpenter. Though the film hadn't done well here in the US, it did very well in Europe and John Carpenter had gained a reputation as an up and coming talent there. Having had a good experience with Carpenter on "Assault on Precinct 13," Yablans contacted Carpenter and asked him if he would be interested in writing and directing a film based on the idea. When Carpenter came back with an idea for the film and claimed he could finish the film for three hundred thousand dollars, Yablans jumped at the chance. He said, "For three hundred thousand dollars, I'll give you anything you want, your name above the title, final cut, whatever. Nobody else would claim to be able to make it for that little," Yablans would later claim.

And so was the beginning of a film which has frightened and thrilled audiences for almost thirty years. Halloween has spawned a cultural icon in the form of Michael Myers, and the classic film is nearly required viewing for teenagers looking for a good scare. John Carpenter and partner Debra Hill wrote a script with simple, like-able characters who we could all identify with. Though the majority of the cast was female, the great thing about them is that we all know girls like Laurie, Annie and Linda. Not to mention that Carpenter managed to make Southern California look like Anywhere-ville U.S.A, it was easy to identify with these characters and their lives. They were near perfect archetypes for All American Girls. Debra Hill was more the influence on the female characters as she had once of course been a teenage girl. But it is Carpenters eye for style, and his contribution to the script of the character of Michael Myers and Dr. Sam Loomis which set Halloween far apart from it's sequels and imitators.

In the films opening sequence we are seeing things through someone's eyes as they spy through a window on a man and young woman making out in a living room. They proceed to head up a flight of stairs holding hands as we watch. We see as the lights go out in a room up stairs and then go around the house, through a back door, into the kitchen, a hand pulling a large kitchen knife from a drawer, and through the house. The young man is seen leaving the house as we continue and then go up the stairs where a small mask is picked up and placed in front of the camera, creating two eyes we now see through. We come to a topless young woman brushing her hair in front of a mirror. When she turns realizing there is a figure standing there (one whom we have yet to see, but whose perspective we are still seeing through), she exclaims, "Michael." With that, the hand and knife swing through the air repeatedly, camera focusing on the hand slashing through the air, not actually seeing her being stabbed, as if the character himself has no idea why he's doing it. Then, when she falls to the floor, we go back down the stairs and through the front door we'd seen the young man leave through earlier. As we come out, a car is pulling up in front of the house. Two people get out and again exclaim, "Michael." The man coming over and removing the mask whose eyes we've been seeing through and the camera cranes back and up, revealing the eyes we've been seeing through have been those of a young boy dressed in a clown costume, bloody knife still in hand.

And so begins the story of Michael Myers. The entire beginning sequence was shot with Steadicam, which at the time was a relatively new invention, and has an incredible effect. It's not only an extremely ambitious shot because of the use of the Steadicam, but also because it's one long continuous shot, which seems to have no cuts. The effect it has is to really make the audience feel as if they are there seeing through the character's eyes. With no cuts, and the movement afforded by the Steadicam, the audience is forced into being a part of the action on screen. It would almost be like a cheap magicians trick if it were not both so ingenious and so effective. The shock of finding out we've been seeing through the eyes of a young child who has just murdered a young girl (who we come to find out was his sister), combined with the fact that the audience is being forced to see things from his point of view are incredible. Carpenter could not have set the stage better either, because there is no exposition, no reasoning behind it, nothing.

Leaving us with no information as to why this child would have just killed this young girl, we are now hooked. We have also been given some very important exposition points with little to no dialogue and a kind of visual vocabulary which continues through out the film. Because of heavy use of Steadicam through the entire film, it does help to give us a sense of a floating terror, which could really be anywhere, watching, and waiting as he was in the beginning of the film. There have been a number of extremely memorable opening sequences in horror history, but none like this one for sheer style, strength, and effectiveness. Even though it was a Steadicam sequence, the composition of the shots was great, the musical cues were haunting, and most importantly, the audience is now hooked. They want to see what happens next.

What happens next is a perfectly paced exercise in suspense. Although it's credited with beginning the slasher film craze which would last through the eighties, "Halloween" has more in common with "Psycho," than "Friday the 13th." Carpenter directed the film to bring out every second of suspense each scene could possibly capture. Michael Myers becomes the doom lurking in the shadow, the bushes, the closet, not the weapon wielding madman chewing through scenery and cast members the way not only the sequels tend to portray him, but all of his imitators tend to be portrayed. Michael is, as Carpenter wrote the character, the manifestation of the bogeyman we've all feared as children, waiting in the shadow or under the bed for us to fall asleep or for our unsuspecting guardians to stop paying attention to us for just one second. Except Micheal's not after the children in this case, he's after the girls charged with being their guardians for the evening. On All Hallows Eve, an evil thing has come out. It's come out of the psychiatric institution a few counties away, but it's come out all the same.

Cast as the unfortunate object of Micheal's attention is Jaime Lee Curtis, then nearly unknown other than a quick stint on televisions Petticoat Junction. Co-writer and co-producer Debra Hill suggests her after Carpenter's first choice, another up and coming young actress turns them down cold because her career seems to be doing too well to star in a low budget horror film released by an independent company. I'm sure she kicks herself later, because after Irwin Yablans, the executive producer finds out Curtis is the daughter of Janet Leigh, star of "Psycho," he agrees immediately. Lucky for us all because Curtis gives a great turn as the young, repressed Laurie Strode. Her shy, intelligent character is impossible not to like and impossible not to identify with. Her co-stars, Nancy Loomis and P.J. Soles (whose role was actually written for her by Carpenter, having seen her in "Carrie" the year before, but not sure she would accept the role), play the wise cracking, strong willed Annie, and the stereotypical cheerleader Linda. Both are great fun to watch as they breath life into what could have been very formulaic and standard characters. Particularly Soles character who, other than the scene in which she meets her end, never finishes a sentence or phrase without saying, "totally." There's also a great moment just before Loomis final scene where she looks directly into the camera with an expression that begs, "Hey, did you notice that," and it's almost a great laugh.

Then there's film veteran Donald Pleasance who plays psychiatrist bent on stopping Michael Myers, Dr. Sam Loomis. Pleasance was offered the job after a number of other actors had turned it down, Peter Cushing, and Christopher Lee included, both having had incredible success with the Hammer Horror films during the decade. Cushing had been in "Star Wars" the year prior and refused the film, as did Lee (who would later admit it was the one move he regretted in his career). Irwin Yablans suggested Pleasance after having seen him in "Will Penny" where he played an eccentric character in the Old West. Pleasance was offered the twenty thousand dollars the budget had set aside to attempt to draw one well known actor to the small project. He agreed to make the film for forty thousand, which brought the total production cost up to three hundred and twenty thousand dollars. Pleasance showed up on set and proclaimed to Carpenter that he didn't know what he was doing there. The only reason he'd taken the job was because his daughter had seen Carpenter's "Assault on Precinct 13," and being a musician had loved Carpenter's score. Considering both Pleasance and Curtis weren't among the director's first choices, and they were both hired because of third party influence, it seems Providence was behind "Halloween" from the beginning.

Speaking of the score, the hauntingly simple piano and synthesizer score for the film was also done by Carpenter. He'd done the score for "Assault on Precinct 13"(which resulted in Pleasance taking on the Shape), and for "Halloween" created a theme and score which like the movie it accompanied was deceptively simple, and yet still unnerving. The theme for "Halloween", that simple piano line has become as iconic as any of it's characters, including Michael Myers, and is so easily recognizable from it's first few notes, only possibly the theme from "Jaws" is more well known. On the second disc for the 25th Anniversary Edition, Carpenter comments that it was "Halloween" which taught him how important music really is for a film because he screened it for some studio executives at one point before the music had been added and it hadn't been scary at all, but after adding the music, it had taken on a much more sinister and frightening tone. The music, like the film and it's villain, is composed to grow in depth and become more overpowering as the film continues. During the films finale, the use of only two bass keys on a piano help to heighten the suspense and create in one scene, a panic which is rivaled by only the greatest of horror films.

The composition in the film is meticulous. From the opening sequence which is incredibly ambitious for a film this size, to the finale, it's shot almost as if it were a period drama, characters all in frame together, few cuts to close ups and with very spare editing which helps to establish the reality by letting us sit longer with the characters in each shot. The less we change angles from the cameras perspective, the less we are reminded, even unconsciously, we are watching a film. One interesting thing about the cinematography of the film is that the early shots of Michael Myers are very wide shots, not close at all. Through most of the first half of the film we can't tell whether the mask he's wearing is even supposed to have features or not because it's too far off. But as the film goes on, the lens pulls in tighter and tighter on Myers, creating a feeling as if doom is creeping closer and closer to the unknowing teens. The use of wide angles, and the very heavy use of Steadicam create a visual vocabulary for the film from the beginning all the way through, and it looks great. It's part of what elevates "Halloween" above it's imitators, it looks as if each shot was thought out and tested long before hand to enhance the almost postcard like look of the neighborhoods and settings of the film. Unlike so many other slasher films, "Halloween" is very pretty to look at for the low cost at which it was made.

Because the story is so simple and straight forward, Carpenters level of technique has to be praised. Like "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre," "Halloween" is often criticized for being too violent and gory. The truth is though that in watching the film, once again, the violence and blood are all off screen. An episode of "ER" or "Animal ER" is more gruesome than "Halloween" because Carpenter was following the example of Alfred Hitchcock, who's now famous approach was that the less you show onscreen, the more frightening it is because the audience fills in the pieces themselves, and they know what scares them better than a director does. "Halloween" is a near perfect exercise in suspense precisely because Carpenter is patient with everything. From the cinematography, to the plot revelations and it's the patience which creates such a thick atmosphere of suspense. "Halloween" is really a masterpiece in film making. It was the most profitable independently released film of all time until the release of "The Blair Witch Project," which although a good movie, did rely on a gimmick for it's success. "Halloween" has been the little train that could for nearly thirty years, and hopefully future generations will continue to see it for it's genius, not for it's few flaws.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments should be respectful. Taking a playful poke at me is one thing (I have after all chosen to put my opinion out there), but trolling and attacking others who are commenting won't be accepted.